In his book, The Flywheel of Life and Leadership, former Caterpillar Group President Ed Rapp recalls taking over a challenged business unit which had never been profitable. “Through a granular understanding of the business, it became apparent that, in each part of the organization, there were no more than a handful of initiatives that, if executed successfully, could play a major role in improving the division’s performance.”[1]

Remember the 80/20 Rule we spent so much time talking about in the opening sessions of the course? Ya, that’s still a thing, and it’s an appropriate time to revisit it.

One of the reasons that the 80/20 principle is so valuable is the reality that human beings— and the organizations they create and operate— are only capable of accomplishing a limited number of things simultaneously. Execution starts with focus, and organizations that try to focus on too many initiatives at the same time usually wind up doing a mediocre job on all of them.[2] The same is true for individuals. You may think you are capable of simultaneously studying for an exam, playing video games, watching a WNBA game and listening intently to the lyrics of your latest Spotify playlist, but you’re not— at least not in a way that allows meaningful performance.

The human brain is actually a very poor multitasker.[3] Your chances of achieve 2 or 3 goals with excellence are high, but the more goals you try to juggle at once, the less likely you will be to reach them.

This tees up two critical concepts that we’ll explore in this final Section of Part 1 of the Course:

1) With many demands on your time, and innumerable distractions pulling on our “monkey minds” (hello, social media!), how can we manage to ensure we are creating adequate time to focus on solving our most important problems? And,

2) The reality is that people inside and outside your organization will continue to offer additional candidates into your “Universe of Opportunities.” To maintain focus, you are going to have to figure out how to say “no.” When and how do you do that?

A. Planning and Protecting Time for Deep Work

Let me start off by recommending that anyone particularly interested in a “deep dive” (pun intended) on this topic should read Georgetown professor Cal Newport’s book Deep Work, and/or subscribe to his podcast “Deep Questions.” Pretty much everything in this section is blatantly stolen from Newport’s work, but most successful people I know were utilizing these simple concepts long before Newport began writing about them.

Most problem-solving— or at least the solving of the important problems that create value for organizations today—require the type of cognitively demanding effort that Newport refers to as “Deep Work.” People who find ways to protect their time and are able to actively engage in this type of work are going to be comfortable mastering the increasingly complex systems and skills needed in our economy.[4]

In many ways, the value you create for your organization is directly tied to your ability to solve problems, which requires significant time for cognitively challenging (“deep”) work. Unfortunately, even though so-called deep work problem-solving is a key differentiator in individual and organizational achievement, most people are surrounded by so many distractions and demands on their time, that they find it very difficult to bring the type of focus required for cognitively challenging tasks— like important problem-solving. As Newport says, “we are driven toward shallow work in an economy that increasingly requires depth.”[5]

In the face of this challenge, many of us tell ourselves, “it’s ok, I’m a really good multitasker, so I can work on shallower tasks while simultaneously solving big problems.” The unfortunate truth is the human brain— while a wonder— is terrible at multitasking. Studies show that when our brain is constantly switching gears to bounce back and forth between tasks – especially when those tasks are complex and require our active attention – we become less efficient and more likely to make a mistake. [6]

However, this type of “multitasking” whereby we attempt to engage in multiple tasks simultaneously is how many people— especially so-called “knowledge workers” –actually conduct themselves at work. We often go from checking email to constructing a spreadsheet to checking TikTok— or some similar loop– over and over again. The time and energy it takes the brain to switch from task to task is significant and it keeps us from being able to engage in the type of deep, cognitively demanding type of thinking that most significant problem-solving requires.

Another inconvenient truth is that while many of us would love to have jobs where we could dedicate ourselves full-time to deep work problem-solving, those jobs don’t really exist. Even if they did, most of our brains aren’t capable of that type of continuous cognitive demand either. In other words, all jobs require a certain amount of “shallow work”[7] and it’s ok, and actually necessary, to give our brain regular “breaks” from cognitively demanding tasks. The problem is many people feel so buried in shallow work that they have trouble creating time for deeper higher-value problem-solving.[8]

Here are a couple tips when you find yourself stranded in the shallows, without sufficient time to dedicate to deeper problem-solving:

1) Look, I know we’ve spent most of the course on this concept, but it’s really important: be intentional about identifying the most important things for you to get done (i.e. problems to solve) in a given period of time (Day/Week/Month/Year), and WRITE THEM DOWN! Be very limited in what you identify as MOST IMPORTANT. No more than 3 tasks per day, 5 milestones per week. (More on this in Section C, below)

2) Then, be equally intentional about ensuring you are creating time to actually get those things done.— one at at time. Newport has a process he calls “Block Planning”. [9] His concept is to start every day by sketching out blocks of time and allocating the main activity for each block. In addition to intentionally setting aside time for your most important tasks, this process brings the additional advantage of minimizing the time you need to spend any day asking yourself, “what should I do now?” In my experience, those are the times that tend to be soaked up by social media and other non-value-added activities. Newport will even sell you a workbook to use as a block-planner, but any notebook, calendar/organizer, or digital calendar will work. As with most of these ideas, embrace the flexibility to see what works best for you.

3) We’ve all been there. You know it’s time to engage in some type of cognitively demanding activity, but you keep procrastinating or just plain can’t “get in the zone.” Sometimes, certain patterns of practice and even physical locations can help speed up the process. Newport refers to these as “rituals”. [10] Selecting a certain office (or non-office!) location for certain types of projects; exploring what time of day you find most productive for “Deep Work”; special snacks or walking patterns to engage in during short breaks; even a certain phrase you might utter to yourself out loud or write down to mark the beginning and end of your deep work session— all these can be effective for entering and staying in the right mindset to attack cognitively challenging problems.

4) Find time near the end of your workday to reflect on what you’ve been working on and ask whether there’s anything you could have done differently to reduce the “shallow work” and make more time for the higher-value problem-solving. We all go through periods where it seems like we just have too much “busy-work” taking up too much time on our calendars. However, for some reason few people go to the trouble of thinking analytically about whether that busy work can be reduced or eliminated. Try tracking what you work on during the day for a given period. Then, go back and look retrospectively at how you spend your day. How much time is spent on really valuable things versus stuff that you feel like you have to do but you’re not sure why. Ask why you’re doing those things (five times!). Can you avoid those tasks in the future? Can you “say no” to them when asked? [spoiler— that’s next!]

B. When and How to Say No

“Nothing is more counterintuitive for a leader than saying no to a good idea, and nothing is a bigger destroyer of focus than always saying yes.”[11]

Our Universe of Opportunities is too vast to accomplish everything we could be working on. Even productive and worthwhile tasks occasionally need to be set aside because there are just more important problems to be working on in any given period. Hopefully, Part 1 of this course has given you an example of an Operating System to help prioritize and determine where to spend your time. Inevitably, though, the things you are not prioritizing are not going to get done— at least not as quickly as someone might expect. Chances are, a lot of those things in the Universe of Opportunities are direct or indirect requests from other people— and potentially people who play meaningful roles in your personal and professional life. So, what do you do when you are asked to take on additional tasks and responsibilities that you don’t have time for?

I’m not going to pretend that there’s an easy way to do it, or even that it can always be done. While there’s no shortage of business and self-help “advice literature” out there, it tends to be awfully simplistic, and contains “helpful” maxims like, “Don’t be Mean, but Don’t be too nice.”[12]

It’s a hard topic— especially for people early in their careers, who happen to be high-performers. The “Curse of Competence” is real and I know I was occasionally guilty of overloading eager young high-achievers in the organizations I led, who became default “go-to’s” for important (and, if I’m totally honest, sometimes unimportant) tasks and projects that I wanted to make sure were handled well. Leaders are often well-meaning in giving these assignments and see them as granting opportunities for high-potential people in the organization to accelerate development and career growth. However, very often, the people assigning these “opportunities” don’t have a holistic view of the person’s workload and how much is on their plate— professionally and personally. Given this dynamic, it’s very easy to get overloaded and fail to adequately address higher-return opportunities.

The good news is there are some common-sense principles that can help people navigate these situations. However, deploying these principles requires you to think in what at first might seem to be a brutally self-interested way. This may not strike some of you as “Iowa nice”, but organizational politics are an important reality to consider in these situations and sometimes accepting the right opportunity (or declining the wrong one) can have significant career consequences.

The first step is to assess the the opportunity by asking at least two sets of questions.

1. Who is making the request? The first factor that needs to be considered when someone is “offering” to load more work on your plate is — who is the person making the request.

Specifically…

- Is the requester my boss? or

- Do I have an important personal or professional relationship with this person? (e.g. Are they a friend? Are they someone who can be helpful in my professional/career development?}

If the answer to any of these questions is “yes”, then the requester may be thought of as “helpful” for purposes of the framework described below.

2. What is it I’m being asked to do? It’s important to understand what you’re being asked to do and what implications it might have for you personally.

Specifically…

- Is this something that will help the organization reach its strategic goals?

- Is this something that will help me achieve my personal performance goals? (Hopefully, there’s alignment between these first two questions.)

- Will this increase my profile and expose me to other people who can help me and my career?

- Is this a topic that excites (or at least interests) me?

If the answer to any of these questions is “yes”, then the subject matter is somewhat aligned for purposes of the framework analysis below. The degree of alignment depends on how many yeses and the importance you place on each question.

The next step is to assess your capacity, by asking questions such as:

- Do I currently have additional time available to productively focus on this opportunity?

- If I don’t immediately have such additional time/capacity, is there something coming off my plate soon that will create that capacity?

- Is there anything I can do to become more efficient or is there something I can stop doing that does not add value to the organization or move me toward accomplishment of my personal goals in order to take on this opportunity?

- Do I have the skillset to accomplish what’s being asked of me? Important to note, if you are being asked to do something by your supervisor or an executive leader in the organization, you should defer to their judgment. If they didn’t think you had, or could develop, the skills to take on the opportunity, they wouldn’t have asked you.

- Is there anything I can do to become more efficient or is there something I can stop doing that does not add value to the organization or move me toward accomplishment of my personal goals in order to take on this opportunity?

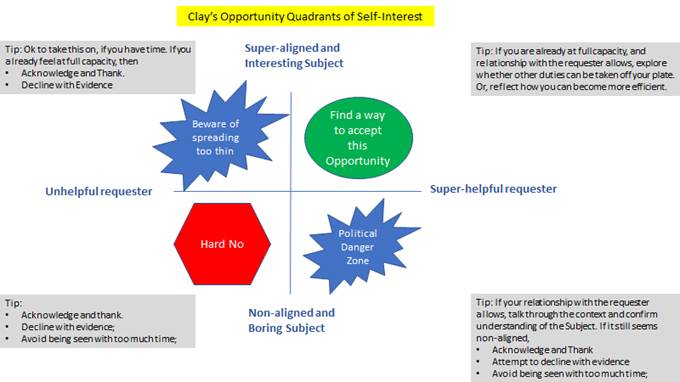

Ok, after the assessment has been completed, it’s time for the hard work. I know none of you are Machiavellian enough to think this way, so I’ve taken the liberty of inventing a chart of self-interest and naming it after myself.

Voila:

As with any analytical framework, this is far from flawless, but I think it can be helpful in considering opportunities in the context of office politics.

The upper right and lower left quadrants are pretty clear. If you get an opportunity from someone who is, or can be, helpful to you, AND the opportunity is highly aligned (as determined via the series of questions above), then you should find a way to accept— even if this means de-prioritizing other potential uses of your time. Similarly straightforward, if you get a request from someone you have no relationship with and they can’t be helpful to you AND it isn’t a subject that aligns with your goals or otherwise excites you— find a way to say no.

The other two quadrants are trickier— especially the one where someone who is or can be helpful is asking you to do something you don’t think is aligned. In this case, it’s important to followup with the requester and get more information. It could be that you are misunderstanding the request and there’s more alignment than you thought. Especially when dealing with someone at a higher status level in the organization or with more experience than you, it’s probably worth granting them the benefit of the doubt here. You don’t want to come off as a “smarty pants” questioning their judgment. Here are some more specific guidance that may come in handy for this type of conversation:

- Start by acknowledging the request and thanking them for the opportunity.

- Explain to them your current workload and be as specific as you can about what else is on your plate.

- Explain that you’re trying to determine how to prioritize their request in relation to the other things you are currently working on and ask them for their insights on the importance of the task to the organization relative to those other things.

There are a number of positive things that might come from this conversation. First, with additional insight and information from the requester, you may realize that the opportunity is actually more aligned than you first thought. Second, the requester may obtain a better understanding of your workload and other priorities and withdraw the request. Third, the requester may provide insights that can help you re-prioritize the tasks currently on your plate.

Even the “hard no” quadrant can be tricky because you never want to be seen as rude and, more selfishly, while the requester may not currently be important to you, who knows what the future might hold? Here are some thoughts on how to say no.

- Acknowledge that you are flattered by the opportunity and thank them for it.

- Cite evidence for either

- you don’t have capacity (and don’t think you could accomplish it as successfully as you wanted because you are fully burdened with other highly aligned activity);

- The opportunity is a bad alignment fit, because

- It doesn’t match your skillset (don’t let this keep you from taking on an upper right quadrant opportunity. If they didn’t think you could do it, they wouldn’t have asked you.)

- It’s outside the scope of your job and might create organizational confusion. (again, if someone above you in the org is asking you, assume this has been thought through and trust her judgment).

I think this goes without saying, but just one final thought— be sure you are being honest with yourself and everyone else in this analysis and these conversations and make sure you are doing everything you can to work as efficiently as possible before turning down any aligned opportunities. If you have to pick between being temporarily overloaded by an organization or having a reputation as being lazy, it’s best to be temporarily overloaded.

C. The Importance of Intentional Planning and Documentation[13]

“The root cause of failure is often not deploying a systematic approach to forming new habits that lead to desired change.”[14]

-Ed Rapp

You can work closely with your supervisor to come up with performance goals that are specific, measurable, achieveable, relevant and timebound and then thoughtfully break those goals into perfectly synchronized milestones. However, if you aren’t in the habit of continually assessing progress toward those milestones and using them and the 80/20 principle to select high-return problems from the Universe of Opportunities, then you will likely be mismanaging your time and suboptimizing. In other words, the most powerful, and difficult, part of any effective operating system is having the discipline to regularly sit down and intentionally plan how to spend your time in order to ensure you are allocating sufficient time and energy to solving your highest-return problems.

This is especially difficult because in a time-constrained environment, often the last thing you want to do is carve out time to plan. However, If you don’t schedule dedicated to intentional planning for this activity (and writing it down!), you will likely fail to solve the highest return problems in your Universe of Opportunities.

I realize that I sound like an old guy when I say “write it down!” The method or tools that you choose to document your cascade are up to you (and may be dictated by your organization), but it’s extremely important that every element of the cascade be documented by either digital or analog means— especially the weekly objectives and daily tasks.

There are a number of reasons for this. First, and maybe most obviously, it will keep you from forgetting. Life and work move fast, and if you aren’t documenting performance goals, milestones and tasks, you are unlikely to easily recall them after a certain period (which reduces with age); and their effectiveness will obviously be diminished.

Having your goals and objectives documented also helps facilitate the application of the 80/20 principle. When things are clearly documented, it’s much easier to ask and answer the question, “what are the critical few most impactful things I can do in order to complete this goal/milestone/task?”

There’s also something about the act of documenting this type of information that simply enhances the sense of commitment. For me, anyway, that sense is heightened if I have to go to the work of writing it down on paper. The good and, in this case bad, aspect of most digital solutions is that they make things easy. For many, the extra inconvenience of having to write out our weekly milestones and daily tasks in a notebook with a pen or pencil creates a bit more emotional commitment to the process.

As with most personal needs in a capitalist system, there are vendors who would love to sell you tools to assist in this process. From elegant Moleskin notebooks and Franklin Planner binders on the analog side to digital tools such as Trello and Microsoft Planner, there are a number of products available, for a price, if you are interested. However, you don’t need to spend much money to adopt these practices. A simple notebook, or an excel spreadsheet or word processing document can be easily adapted for the function.

The most important enabler of success in creating your personal system— much more so than the tool you select– is being intentional about creating a habit to execute this practice. It’s very easy to get so engaged in your work or other aspects of life that you find yourself jumping every morning directly into answering email, instant messaging or diving headlong directly into whatever project is on the top of your mind as the day starts. I highly encourage you, though, to be intentional about setting aside time on your calendar to ensure you are engaging regularly in the practice of setting and evaluating and updating your glidepath milestones and daily tasks.

This is the standard work— touched on previously in Section II.A.3 that works for me. :

- Early January:

- Allocate at least two hours to examining my organization’s Mission, Purpose and Strategic Plan and then develop and document 3-5 individual SMART Goals which are:

- Challenging but achieveable; and

- Aligned with the organization’s strategic plan.

- Allocate at least two hours to examining my organization’s Mission, Purpose and Strategic Plan and then develop and document 3-5 individual SMART Goals which are:

- I set aside time on my calendar on the appropriate dates for monthly and weekly steps described below.

- The first (working) day of every month:

- Allocate one hour to assessing the status of my annual SMART goals. Are they still challenging and achieveable? Is any change necessary?

- Then develop and document 4-6 “Glidepath Milestones” that must be accomplished that month in order to keep me on track to accomplish my annual goals.

- Beginning in the second month of the year, I also review the Glidepath Milestones I documented for the previous month and for those that haven’t been accomplished, ask why? (5 times?) What can I learn or adapt going forward?

- Reserve on my calendar for that month any time necessary to accomplish these milestones, including setting up key meetings. (following the “Meeting Hygiene” principals set out in Part 3 of the course.)

- Every Monday:

- Allocate 30 minutes to reviewing the status of my Glidepath Milestones for that month. Have I learned anything in the last week that might cause me to revise these Monthly Milestones?

- Identify 3-5 critical tasks that must be accomplished that week in order to allow me to accomplish the Glidepath Milestones by month end.

- Review the status of last week’s critical tasks and for any that were not completed ask why (5 times!); What can I learn or adapt going forward?

- Ensure that sufficient time is reserved on my calendar for that week in order to accomplish the identified tasks.

- Every (Workday) morning:

- Allocate 15 minutes to identifying 3-5 daily tasks or “micro-steps” that I need to accomplish that day in order to accomplish my weekly tasks.

- Review the daily tasks I set for myself yesterday and for any that were not completed ask why (5 times); what can I learn or adapt going forward?

- Review the day’s calendar and see if any adjustments need to be made in order to have sufficient time to complete my daily tasks or micro-steps.

Reflection Questions

Most successful college students understand the importance of focus and “deep work” time required for certain types of studying.

- What are some of the college/class related tasks and activities that you find require significant cognitive focus?

- What are some of the things you do in order to ensure you have the right conditions in place for this type of work?

Have you ever yourself taken on too many priorities and therefore failed to accomplish them. Any examples of someone else (real or fictional) who fell into this trap?

What were the root causes?

What can we learn from that example?

Do you have any examples of things you “signed up for” or agreed to do that didn’t wind up getting enough attention?

Why did you commit and what were the consequences?

How would you handle it differently if you could do it again?

Is there anything you could/should have “taken off your plate” so that you could have pursued this opportunity more fully?

What are the most important 3-5 things you want/need to accomplish this academic year?

Are there 3-5 things you should do this month in order to maximize your chances at success?

Have you intentionally set aside time for those things?

Anything that needs to get done this week?

Today?

[1]. Rapp and Jain, The Flywheel of Life and Leadership, P. 82.)

[2]. McChesney, Covey, Huling, The Four Disciplines of Execution, (2d ed) p. 34.

[3]. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/science-clear-multitasking-doesnt-work/

[4]. Newport, Deep Work p. 37

[5]. Newport, p. 60.

[6]. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/science-clear-multitasking-doesnt-work/

[7]. Defined by Newport as “Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted.” P. 6.

[8]. Also, most “shallow work” is (a) not particularly valuable for organizations; and (b) relatively easily automated, especially in a our new age of AI.

[9]. Newport, p. 223

[10]. Newport, 117-118

[11]. The 4 Disciplines of Execution, McChesney, Covey and Huling, p. 35

[12]. HBR Guide to Being More Productive. Knight “How to Say No to Taking on More Work”; p. 74

[13] : I’ve gone back and forth on whether this sub-section should appear in Section II of Part 1 of the Course Guide or here in Section III. A lot of this subsection has to do with implementation of the Management by Objectives Operating System we covered in Section II. However, it also arguably belongs in here in Section III because careful and intentional planning is critical to creating sufficient Deep Work time

[14]. Rapp and Jain, The Flywheel of Life and Leadership, p. 93.